Understanding the context of how people earned and spent money during the early modern era gives an insight into this magnificent mourning miniature.

Jewellery, like all art and design, ranges from the exquisite to the allowable. Societies are driven by the appreciation of aesthetic quality, especially those who can afford to buy objects that fund artists to produce them. Even at its lowest level, people still have the desire to have a jewel created. Colonel Robert Walpole (1650 – 1700) left behind 72 mourning rings at £1 each to friends and family, roughly a century before this miniature was created. Consider this cost at a time when Peter Earle’s calculations suggest that a “middling” family with two servants and a total income of £200 probably had something like £16 of discretionary spending power for the year.” Giving the gift of a mourning ring at a funeral during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries was a common custom, often expected from the higher levels of society. During the 19th century, the allowance of lower grade alloys and mass production dropped the prices of mourning rings to as low as 21 shillings, as advertised in Eddowes’s Journal 1857.

To achieve the quality of miniature portraits in the 18th century, miniaturists focused on their own methodologies for improvement. The above mourning miniature example shows the pinnacle of the Neoclassical period, with the subject beautifully rendered in soft tones. This could not have been possible without innovation. Bernard Lens, c.1707, was the first British artist to paint on ivory, as the previous popular material for painting was vellum. This allowed for the canvas to become smaller and jewels could adapt to these smaller sizes. Enamel portraits were small and popular, while the watercolour on ivory allowed for more detail on a smaller space, while on vellum, capturing detail was harder. Miniature painting became a pastime, rather than a learned skill until the 1760s. Changes in the development of the paintings included roughing and degreasing the ivory, as well as stickier paints. William Shipley (1715 – 1803) founded an arts society in London, which developed into The Royal Society of Arts in 1754, the first school of its kind in London. Young students enlisted, such John Smart and Richard Conway, who would influence the art that was to come.

Cypress

Known as the ‘mournful tree’ by the Greeks and the Romans, the tree was sacred to the Fates and Furies as well as the rulers of the underworld. The tree would be planted by a grave, in front of the house or vestibule as a warning against outsiders entering a place corrupted by a dead body. Romans would carry branches of cypress as a sign of respect and bodies of the respected were placed upon cypress branches previous to interment. It is such for reasons as this that the tree still survives in the Muslim world and in Western culture, the cypress designates hope, as the tree points to the heavens. Here, there is a great continuity of usage for the tree, as despite its cultural interchange, it still remains understood for the same purposes in death.

It is the usage for its heavenly motif that we focus on for jewellery in the Neoclassical era, as the period of around 1760 is when the symbol came into regular mourning depictions, painted on ivory or vellum. The cypress is mostly shown in the background to the willow in the foreground of a mourning depiction, as the mourning woman would often interact with an urn, tomb or willow, but rarely with the cypress itself. Due to is constant usage in cemeteries and reflecting the classical usage of planting a cypress upon death, the cypress is still most commonly seen at the graveyard and the mourning depictions of the tomb or urn on plinth are reflective of that. The cypress’ seen flank the cemetery as they would in reality. Other depictions of the cypress may be the lonely cypress on a rocky outcrop or a singular cypress surrounded by other mourning symbols.

Classical Woman

If you see a woman weeping at a tomb or plinth, this is considered to be the mourning ‘widow’ / ‘grieving woman’ / representation of the Madonna. The woman was the focal point of the family and considered to uphold the virtue of the house, hence why the focus of mourning has been centred on the matriarch. So, considering the woman to be a ‘widow’ is somewhat incorrect (as often many say she is the ‘weeping widow’), as a mother or female relative or friend may wear a piece depicting an idealised woman for a person other than a husband. So, would a female wearing a mourning woman be wearing an interpretation of her literal self? For the purpose of this little overview, we won’t consider the literal matriarchal paradigm throughout the 16th to 19th centuries that I would generally cover of the woman and considering that we’re only looking at the woman for the brief window of Neoclassical depictions, the woman is the Neoclassical ideal and should be considered as such. But is that ideal simply ‘grief’? Let’s take a look at some variations and what to do when in doubt.

If the woman is pointing upwards, it is a sign of faith and hope of the heavenly passage, also denoting that the soul of the loved one has departed.

If you see her hanging onto a cross, this is faith and fidelity. This can be seen in the “Rock of Ages”, written in 1763 by the Reverend Augustus Montague Toplady;

Nothing in my hand I bring,

Simply to thy Cross I cling;

Naked, come to thee for dress;

Helpless, look to thee for grace;

Foul, I to the fountain fly;

Wash me, Saviour, or I die.

The imagery is quite self explanatory and the depiction described is found more in funeralia, unless the woman is clinging to a pillar or anchor, which is more common in mourning miniatures and blends its symbolism with the direct sentiment of grief, fidelity and eternal love in the woman and inserts the symbol that she is interacting with. For example, consider that the woman is the primary/personal symbol for the mourning or sentimental piece and then look at how she is interacting with the symbols around her (secondary symbols). Is she sitting, looking at cherubs take the soul of a child off to heaven? Is she leaning or draped over an urn or tomb? Is she standing with her head turned, holding an anchor? Note the secondary symbols here and how they can represent a child, parent, husband, friend or simply the essence of an emotional allegory or sentiment. Here, she is the ideal symbol of the person and may not simply be grief itself, but the wearer can relate to her, regardless of gender.

One must also analyse the look upon the woman’s face to pay attention to her demeanour; is she crying, sad, stoic? Is she standing, sitting, looking up? Is there more than one woman on display? Many pieces were pre-designed and simply customised in the 18th century, whereas others were created originally at the prerogative of the person who had it commissioned, so the woman can often be quite naively painted or she can be one of the most detailed figures in a miniature. This is a testament to the importance of the figure in Neoclassical mourning pieces. Perhaps the woman (or women) depicted are part of a religious allegory (be it Greek, Roman or having Christian allusions), beyond the simple interpretation of the Madonna. Of course, depending on region, much of the Neoclassical symbolism was represented in different manners.

Throughout the Continent, you have a greater influx of Roman Catholic, Eastern/Oriental Orthodoxies and Protestant influences that didn’t have the more isolated Anglican control of Britain, hence the is a lot more movement for interpretation of the woman as depicted. She is a motif that has been interpreted in other ways by other cultures dating back to pre-history. From the nature that the woman is the one who bore us, the sign of fertility and as a focal point from where life springs from, her interpretation must always be considered first. Look to the depiction, note its point of origin (French, English, American, perhaps an Italian cameo) and begin interpretation of her based upon cultural relevance. This can push aside basic notions of her simply there for the purpose of mourning and shed an entirely new light upon what the woman is doing in the scene.

An example of this is perfectly captured in this French ring. On first look, the ring’s depiction is unlike the basic grieving figure that we take for granted. Simply considering this as such defies the very nature of the piece. What we can make of it, however, is she has two phrases written on her dress; upon the collar is “Longe et Prope” (far and near), and on her hem, the phrase “Mors et Vita”. Upon her head, she is crowned with myrtle (like friendship, evergreen) and pomegranate flowers (concord and internal union) and she is also barefoot (for friendship knows no inconvenience too great for it). Next to her is an elm tree, depicted dead/lifeless symbolising that one true friend does not abandon another in distress, and true friendship is based on mutual support and interdependence.

With her right breast exposed and the arrow having found its way to the heart, she offers this to death, who reaches out to accept. As the statement is one that is very actionable, ‘I ALONE CAN HEAL’, the message of the jewel is designed around suddenness and grief. In the idyllic scenario, there is a very strong feeling of emotional impact. The female here is depicted in classical garments and fashion, from her sandals to hair style. In the drapery of her dress, she is seen with the exposed breast, which alludes to a form of violence:

“…when the breast of a Classical Amazon or Noibid is divested of clothes, it is ostensibly occasioned by action and does not simply result from fashion, i,e a garment designed to expose the breast. Their bared breasts, above all, represent a potent visual convention employed by Classical artists to denote female victims of physical violence… Yet the female breast divested of clothes was a popular motive in Classical art, and the known representations may be divided into four categories. Certain female activities that involved either (1) breast-revealing garments or (2) divesting the female breast of concealing draperies are occasionally represented in art: running, particularly in cult celebration, and breast-feeding of children… Purposeful breast baring (2) belongs to the iconography of supplication, e.g, for mothers of grown sons… yet the earliest and broadest context for divesting the breast of clothes in Classical Greek art consists of representations of female victims of physical violence.” – Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, Claire L. Lyons, Naked Truths: Women, Sexuality, and Gender in Classical Art and Archaeology

She is surrounded by the two love birds and the expression of grief from the cherub/putti figure add to the values of love that have been lost. She is the ideal and the figure that is offering the heart, while remaining the strength of the symbolism. All this design is kept behind a curtain, which has been revealed for us to peer through and see what the impact of death and grief look like for the late 18th century person in mourning.

Not all female jewels were based on allegory. In the above mourning miniature, a lady is depicted in her actual mourning dress. This shows a personal memento of the female mourner depicted directly into the scene itself. This piece reflects upon a literal representation of the woman and in this case, its intent is more of a portrait with the intent of grief, rather than the idealised ‘symbol’ of grief. Whereas, the piece shown here is an idealised symbol that can be represented for both men and women.

Crown

Crowns are a common symbolic theme in late 18th and early 19th century jewels, most popular of which can be found on the ‘Georgian Heart’ jewels of this time. A crown flanking a heart is a simple symbol of veneration of the love for someone. In this instance, the crown is being held by an angel, waiting for the soul of the child to enter heaven.

Linking the crown to the ‘Five Crowns’ or the ‘Five Heavenly Crowns’ is another symbolic meaning that could be attributed to the miniature design. This is due to the meaning being about the reception of a crown after the Last Judgement for those who are worthy. There are five biblical references of virtue to the crown, which have been interpreted as five seperate crowns that need to be earned in order to be received in heaven. There is the Crown of Life, the Incorruptible Crown, the Crown of Righteousness, the Crown of Glory and the Crown of Exultation.

Angel

As the ‘messengers of God’, angels are commonly thought to fit into the paradigm of Judeo-Christian, which is quite acceptable, but their transcendence in art and their ubiquitous use (even through the less-overtly religious Neoclassical era) is given to their focus as spiritual beings. Furthermore, their presence is a clear statement of the afterlife, protection and an acknowledgement of the spirit after death. From the earliest Christian depictions of the iconic ‘angel’ (with wings), angels became one of the more prominent foci of ecclesiastical art through to the early modern period of the Renaissance and Enlightenment. From this, the angel in memorial art is still used today, greatly connected to funeralia and its symbolism.

Two angels: Can be named, and are identified by the objects they carry: Michael, who bears a sword and Gabriel, who is depicted with a horn.

Blowing a trumpet: (or even two trumpets) representing the day of judgement, and Call to the Resurrection

Carrying the departed soul as a child in their arms, or as a Guardian embracing the dead. The “messengers of god” are often shown escorting the deceased to heaven.

Flying Angel: Rebirth

Many angels gathered together in the clouds: represents heaven.

Weeping: Grief, or mourning an untimely death.

Soul of the Child

The child’s soul is reaching towards heaven and awaiting his crown, which represents the purity of his soul. This is in the eyes of heaven and his mother, who watches from below. Wearing the white gown is typical and symbolic of the child who has passed away. Seeing the actual soul of the loved one, rather than the elements of mourning that represent their body, such as the urn, is an insight into the family values of the person who commissioned this miniature.

Symbolically, this is the purest element of the mourning depiction. It is the deceased as they were remembered by their loved one. How this image of their facial features was captured is lost to time, or it is an approximation by the artist.

Tomb, plinth

Male and family mourning jewels are often more immediate to the subject of the mourner in the 18th century. This isn’t to say that the depictions of the male/family in-situ are a literal display of the gentleman and children in the scenario, but that they are more defined because of their time. In the use of the tomb, the tomb is still allegorical, as are plinths, when shown in a jewel like this.

Using the tomb in a Neoclassical setting was popularised, just as the urn/willow combination were, as seen in the Tomb of Werter.

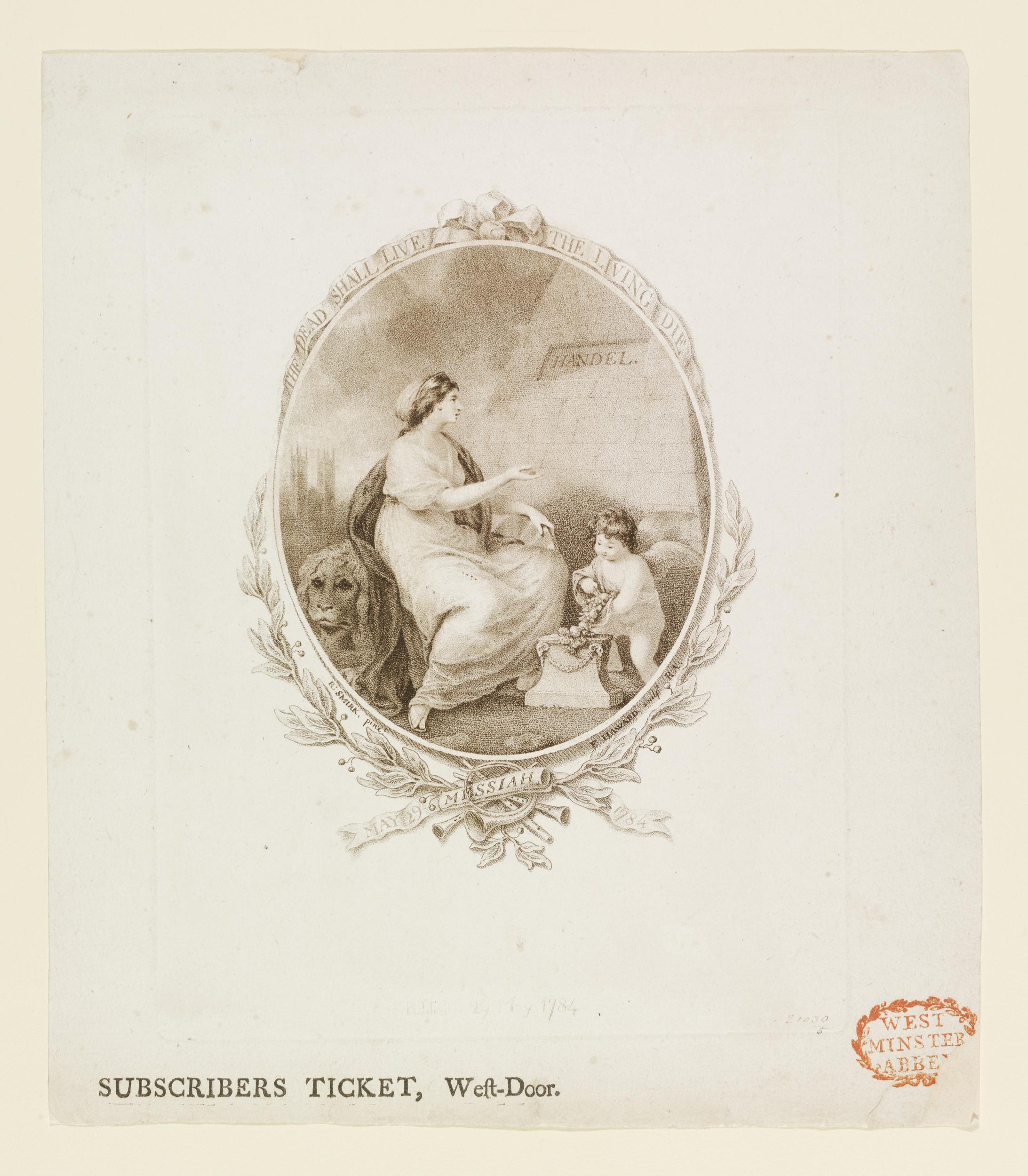

Subscriber’s ticket for a Handel Commemoration Concert of Messiah on 29th May 1784. For the ‘West-Door’. A central ovoid design, featuring a woman and cherub next to Handel’s tomb, framed with foliage and a banner. Etching and stipple engraving.

This ticket relates to the design E.1228-1948 in respect of the principal figure at the tomb but there are many differences.

An example of this can be seen in George Frideric Handel’s ‘Commemoration’ in 1784, which was an event to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the composer’s death. Symbolism in the design of the ticket utilised the popular motifs of the time, complete with religious symbolism in its mourning values. With art by Robert Smirke and engraving by Francis Haward, the inscription of ‘THE DEAD SHALL LIVE / THE LIVING DIE’ reflects chorus of Handel’s Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day (the following line being ‘And music shall untune the sky’). The female figure is once again flanked by the cherub, who is placing flowers on the plinth and has a sad expression. The female has a lion behind her, reflecting resurrection (as there was a belief of lion’s sleeping with open eyes having a comparison with Christ in the tomb) and the tomb to the right. Compare this symbolism and design with the following pin:

French hair and sepia painted memorial, displaying the tomb in front of a willow.

Dominant, square and pyramid shapes of the tomb refined down to the elements of the grave As can be seen in this 1849 memorial, the style is similar, but the stepped tomb is designed more like that of a cenotaph. Regardless of the elements, having the tomb displayed in a mourning jewel or depiction is an important connection to the loved one and their remains.

The Willow

The weeping willow is heavily symbolic of grief, sorrow and mourning, even physically, it stands as an analogy to human grief, with its back bent over the subject, be it a weeping figure, a tomb, plinth or any other mourning subject. Flanking the left side of a mourning jewel in the Neoclassical period was typical for this element of symbolism. From an artistic perspective, it was important in that its leafs could be painted in a border that would frame the image, rather than being a background element in the Neoclassical depiction. This low hanging element, related to sadness, made it the perfect encapsulation of mourning for its time.

The development of the willow in its design went from the element of the tree to the physical viewing of the branches and the trunk. Much of this has to do with the structure of the Neoclassical shapes that encompassed the jewels, themselves. Painted on ivory or vellum, the allegorical situations that were painted needed to be adapted for their design. The high, north to south navette style grew from the oval styles of the 1770s and gave the painter a larger canvass to work with.

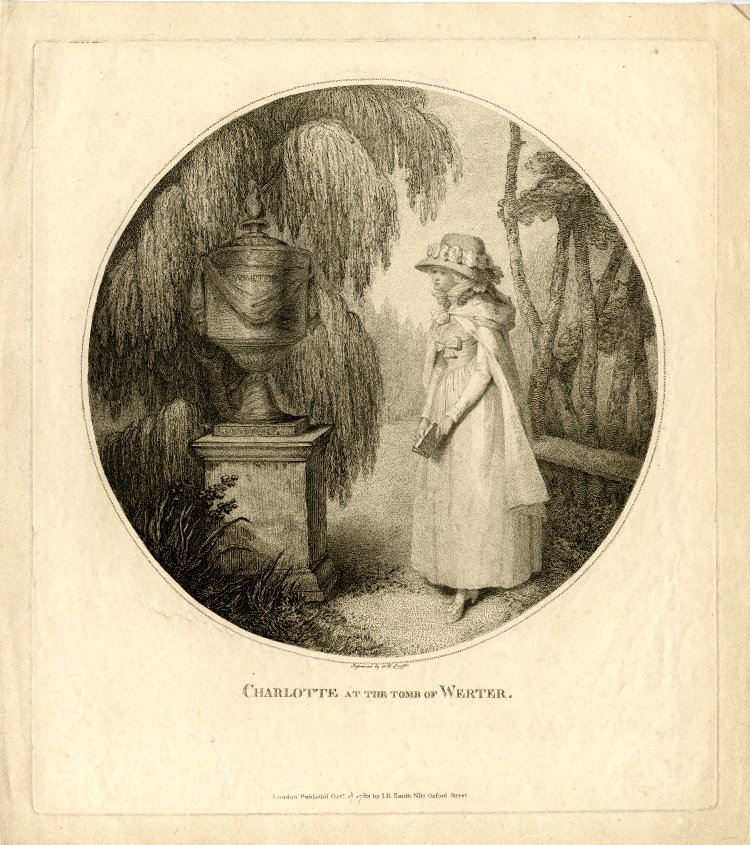

Popular culture grew the elements of mourning symbolism, so much so that Johan Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, published in 1774 and revised in 1787, was important to the Romantic movement, so much so that even Napoleon Bonaparte carried a copy with him during the Egyptian campaign and wrote a soliloquy in the style of Goethe. Its story involves the titular protagonist committing suicide over unrequited love and being buried under a linden tree. The popularity of this book generated much popular fiction and instilled the symbolism of the weeping female character next to the tomb and the willow, as seen by the following ‘Charlotte at the Tomb of Werter’, 1783:

Popular culture is the most effective way of creating identity within symbolism. If there is a cultural movement or predilection of style that is used in a way that can create an icon, such as the willow here, then it will become a symbol that crosses cultures. Considering that Napoleon himself was a fan of the work and Napoleon defined the classical style through jewellery, then popular culture can drive the message of mourning beyond a religious or monarchial figurehead.

In this ring from 1785, the willow is displayed in its full depiction. As a standard of the sepia jewels that were created at the time, this is a pristine example of the symbolism that was popular in mourning jewels during the 1780s.

Deep brown hues and reds to symbolise the earth and the blood are utilised for symbolic effect. Hair was often chopped and mixed into the paint for even greater sentimentality; the person who was being remembered for whatever capacity became the jewel itself.

This is where it’s important to factor in the ideals of what the Neoclassical movement was. This was a time when the classical Greek and Roman sculptures, art and views on philosophy had a rebirth in a time that was primarily dominated by ecclesiastical means. There needed to be a way to show this art and present it upon the person, rather than simply a work of art in a house, the person became the figure to display the art. This relates back to the nature of the person and their role in sentimentality and mourning. The person was not something to be judged at death with a firm control of living inside the paradigms of piety to have this final reward, but the person, and the family, were the targets for grief, mourning and essentially love. Being able to display this affection through the use of Neoclassical philosophy was a major turning point for Western cultures.

Sepia was ideal for this, it involved all the principals for love and it upheld the affectation of the late 18th century perfectly.

Age wasn’t a factor in the usage of the symbolism, either. To be so firmly entrench in the mainstream mindset, this ring shows that no matter what the age of the person who was being mourned was, they still upheld modern fashion. “Prepare to Follow”, a sentiment of notice for those to be aware of their mortality, is used for William Wilton, who died at age 51 in 1785 (which, for a mortality rate of around 40, is quite a decent year). More importantly, William would have been reaching his maturity during the height of the Rococo period and none of those motifs are reflected in the ring.

Pearls

At the second stage of mourning, black and white gems were permissible, which allowed for pearls and jet to become popular at this stage, particularly by the early 19th century. From the 16th century, pearl trade had increased, with trade routes opening up Europe to pearls from India, the Caribbean and the Persian Gulf. The trade centres of Lisbon and Seville increased the ability of the mourning industry to adopt pearls for the second stage of mourning. Jewels utilised pearls as the singular element, or as an addition, which was a contrast to the harsh black that had been used solely in the first stage. Pearls were accessible and had been used for lower grade gold jewels, particularly in the 19th century, allowing them to be adapted well to mourning jewels, particularly in terms of affordability.

Pearls are often referenced in mourning jewels as symbolising ‘tears’, however they were used prolifically in other jewels and take on other conventions for their meaning.

Enamel Colours

Jewels from the c.1550-c.1760 period, outside of the colours black (death), white (virginity/purity), blue (considered royalty) and red (passion), need further interpretation, but in the late 18th to early 19th century, there’s more clarity in what their meanings are, due to studies and publishings of the time.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Theory of Colours is an important resource for the mourning jewellery collector, as it details much of the colour theory that would influence the style, construction and fashion of mourning and sentimental jewellery.

Published in 1810 (German) and 1840 (English), the book is not a reference for sentimental meaning, but a scientific approach to how colours were perceived. The book does deal with shadows, refraction and light spectrum, but applies this to how the human mind processes the data. It was a rebuttal to Issac Newton’s optical spectrum based on Goethe’s own findings.

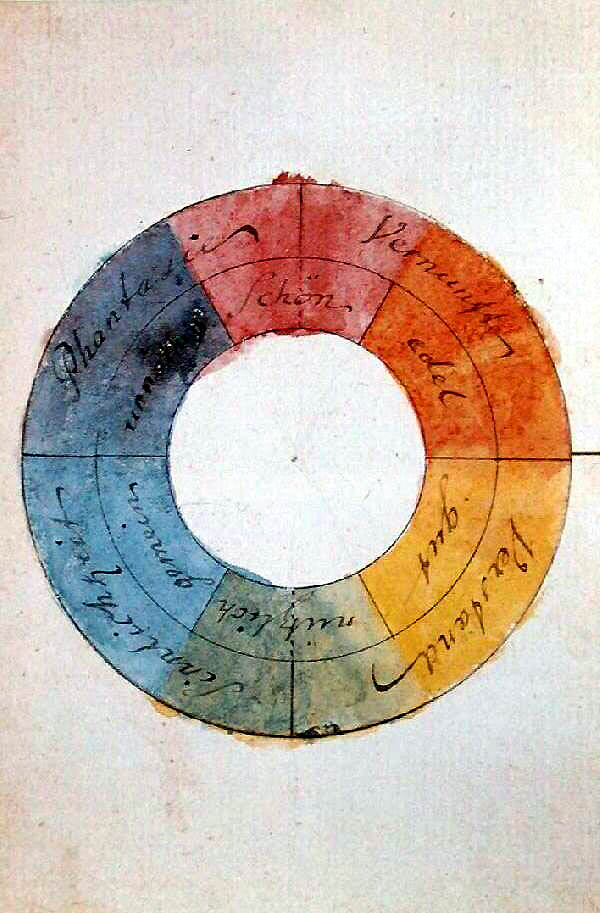

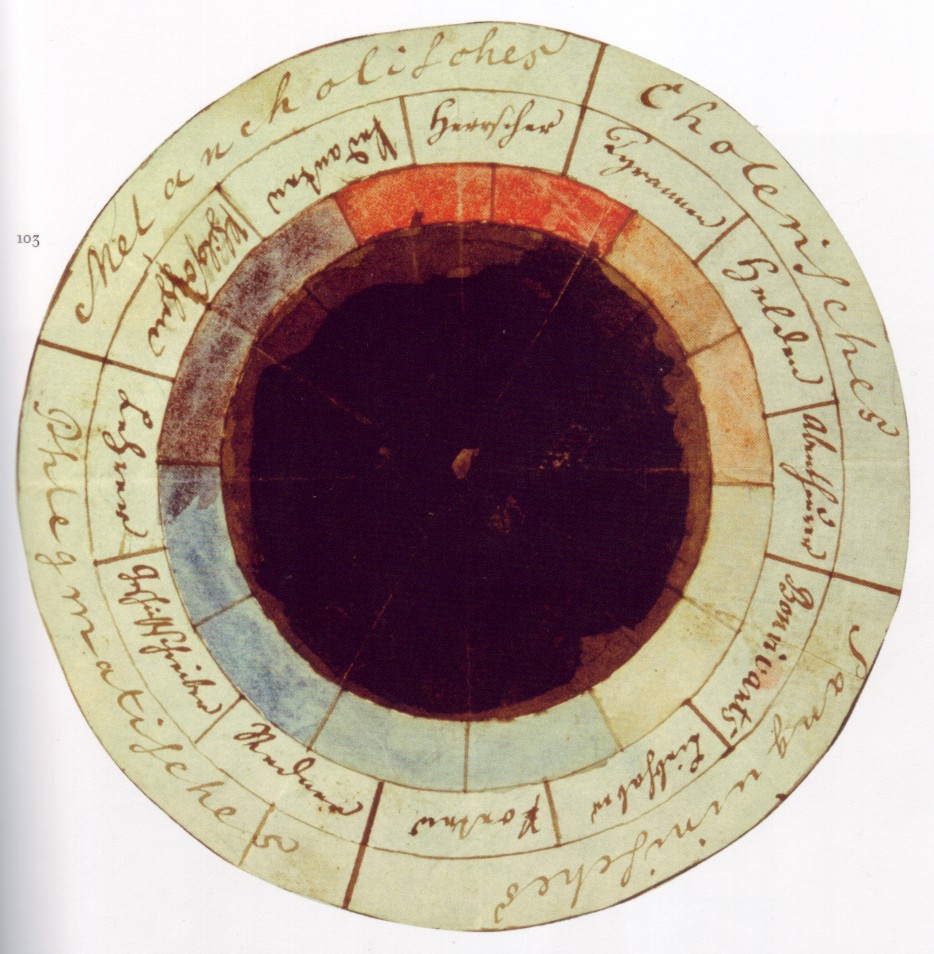

Colour and psychology come together in Goethe’s theory, through the theory that colour provokes emotion. His symmetric colour wheel (below) shows that each colour demands the complement of a correlating colour, as the gradients go down, they still relate back to the parent colour. Goethe’s theory highlighted the important of magenta, which can be seen at the top of the chart:

Goethe and Schiller developed another chart, “allegorical, symbolic, mystic use of colour” (Allegorischer, symbolischer, mystischer Gebrauch der Farbe), which linked colours to psychological reaction. The effect of this was important for the arts, fashion and jewellery.

While the controversy about Goethe’s work was its challenging of Newton, he was a popular figure in the late 18th century for his literary and scientific work. The effects his 1774 book, The Sorrow’s of Young Werther influenced mourning symbolism in its use of the willow and urn, which were taken from Neoclassicism. As the book spread across Europe, so did the common symbols in its publishing, making them common and fashionable.

Original Box

Finally, the original velvet compact box of this miniature shares the last insight of the person who commissioned this miniature. We originally looked at cost involved with making mourning jewels and how this was for the upper echelon to afford. It’s abundance of design and materials, in a time when these things were becoming scarce, shows that the family came from wealth.

In these compact boxes, the miniatures were easy to travel with and not often worn. They could be opened, displayed and appreciated for their art. They are delicate and suffer from impact and movement, as the ivory and pearl elements can come apart, so the box provided an extra level of protection to keep the precious interior safe.

Courtesy: Elizabeth Potts @themoonstoned

Original Article at:

https://artofmourning.com/2019/12/06/breaking-down-the-symbols-in-a-neoclassical-miniature/